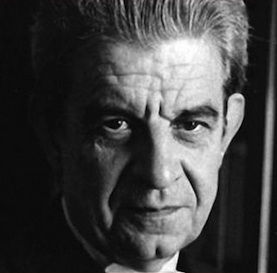

JACQUES LACAN by Massimo Recalcati (I)

- Noé Toledo

- 2 days ago

- 4 min read

Psychoanalysis does not seek to foresee the course of history nor to arrange its events under a progressive logic. There is no naturalistic chronology here, nor any promise of a future that can be read in advance. In Lacan, history does not present itself as an objective account of what has happened, but as an always unstable construction, dependent on language and on the subjective position from which it is enunciated. Without speech, there is no history: there is only a mute succession of meaningless facts. It is language that introduces order, but also rupture.

For this reason, it is less a matter of remembering than of rewriting history. The past is not closed; it is the future — that which has not yet occurred — that retroactively resignifies what we were. Past contingencies are reorganized from the needs that open toward what lies ahead. History is not memory, but work; not an archive, but an operation. Years later, Lacan will play with this idea through the slippage between history and hysteria, emphasizing their dialectical link: history speaks because something does not add up, because there is a remainder that insists.

This conception distances itself both from individualism and from self-determinism, but also from a purely collective reading. Lacan rejects the illusion of a universal science of the subject. Psychoanalysis is, in any case, a science of the particular: not because it ignores the social, but because it understands that the social only becomes embodied in singular forms of desire and jouissance.

From here, the different clinical positions can be understood. The neurotic is defined by the renunciation of the drive: his unconscious is structured like a language, and it is there that his conflict is played out. In psychosis, by contrast, there is an excess of drive reality and a failure in symbolic mediation; the normative fails to operate as a limit. In schizophrenia, the symbolic does not succeed in organizing experience, leaving the subject exposed to a radical fragmentation. These are not labels, but different ways of inhabiting language, the body, and jouissance.

Desire, for Lacan, is not a need nor a conscious will: it is always the desire of the Other; it is constituted in relation. Jouissance, by contrast, is a relation with oneself; it does not aim at encounter, but at the satisfaction of the drive in its closed circuit. Jouissance is useless; it does not produce, it does not communicate: it insists. Hence, its proximity to the drive, which does not seek the Other but its own repetition.

Here, the ethical tension that Lacan reads in Kant and Sade appears clearly. If in Kant, the law presents itself as moral duty, in Sade, the movement is radically inverted: jouissance becomes a duty. It is no longer a matter of limiting desire in the name of the law, but of submitting masochistically to the demand to enjoy. Both positions are two sides of the same coin: law and jouissance do not oppose one another; they can coincide in a deadly way. This logic resonates strongly in contemporaneity, where the mandate to enjoy, perform, and expose oneself presents itself as freedom.

Desire is organized around an object that is never fully possessed. The object looks back: it is imaginary, that which desire pursues without attaining. The little object a, by contrast, is not the object of desire but its cause; it is not a thing, but a function that precedes the subject itself. We do not desire because we are subjects; we are subjects because something is lacking.

In fetishism, desire becomes captured by that little object a. In melancholia, by contrast, that object is experienced as definitively lost, leaving the subject identified with loss itself. In both cases, the problem is not the object, but the impossibility of doing something with a lack.

Language renders the existence of the Thing impossible, just as the phallus renders sexual relation impossible. The Name-of-the-Father does not guarantee harmony or natural order; it introduces a double condition: the signification of the phallus and the limit of jouissance. It is not the child who must traverse the violence of a castrating father; it is the subject, insofar as a speaking being, who is compelled to experience jouissance as impossible. It is language that prevents the drive from becoming absolute law.

Hence, psychoanalysis does not promise a just relation to the real. There is no correct measure nor universal norm capable of ordering desire. The subject’s desire, in its radical difference, cannot be reduced to an ideal acceptable to all. Analytic ethics does not consist in adaptation, but in freeing the subject from the weight of guilt that arises from alienation to the ideals of the Other. Lacan is unequivocal: the only possible guilt is that of having betrayed one’s own desire.

Encounter, then, is not the fusion of two subjects nor the sum of two jouissances. It is not a matter of joining the jouissance of the One with that of the Other — always heterogeneous —, but of articulating, in each subject, desire and jouissance without one canceling the other. Encounter occurs through the crossing of two unconscious knowledges, not through conscious harmony nor imaginary complementarity.

At this point, feminine jouissance introduces a decisive opening. It is not exhausted by the phallic nor organized solely around the object; it always implies a relation to lack. It is not a matter of occupying the place of the object in the sexual relation, but of not retreating before the lack of the Other. A woman who knows how to enjoy and make the phallus enjoy is not hysterical in the Lacanian sense: she does not remain fixed in the position of object, she does not reduce the bond to a scene of demand. Her jouissance always implies relation, non-closure, the impossibility of closure.

Love, from this perspective, does not appear as a complement nor as a fusion. It can only arise when two subjects renounce making the little object a, the center of the relationship. To love implies relinquishing something of jouissance so that desire does not remain fixed or idealized. There is no guarantee, no promise, no closure. Only the — always fragile — possibility of sustaining desire without turning it into a mandate, and of accepting that every relationship is inevitably founded upon a lack.